3 Minutes with Karen, editor of New Worlds, Old Ways: Speculative Tales from the Caribbean

Original Photo by James Wheeler from Pexels

Award-winning author Karen Lord takes a turn as editor in New Worlds, Old Ways to lovely effect. She also closes out the 3 Minutes series for the Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic storybundle which ends in just a couple of days (July 2nd).

Describe this work in 3 words.

Ancient, modern, futuristic.

Editors, what’s your general approach to choosing works for an anthology?

First I select for quality. Second, I select stories that contribute to an overarching narrative or theme.

The world is awash in terms right now: Afrofuturism, Africanfuturism, Black Speculative Fiction, the Black Fantastic, Astroblackness, etc. Do they matter? If so, do they do justice to the diaspora? If not, how might we as authors and editors lead a change? Feel free to offer any new terms you think would expand and/or deepen the concept.

Caribbean speculative fiction is the most accurate term for describing this anthology, as it contains works by writers of African, Indian and/or European heritage who participate in and identify with the culture of the Caribbean. That culture is a blend of cultures: Indigenous, African, European, Indian, Chinese and more.

What are you working on now?

I am collaborating with Tobias Buckell on an anthology of original stories/poems and reprints on the theme of Caribbean futures.

What compels you to keep writing/editing?

The literature we create and curate today will speak to this generation and the generations to come.

3 Minutes with J.S., Author of Queen of Zazzau

Original Photo By Breston Kenya from Pexels

Kicking off the final week the Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic storybundle will be available, we have J. S. Emuakpor to share her views Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic mean and could mean as well as more about her work.

Describe this work in 3 words.

African history reimagined.

How do you define Afrofuturism?

Afrofuturism is not so easy to define, because it is both a noun and a verb to me. It is a movement as well as a product. Afrofuturism is what lies ahead for the African diaspora. It’s our endpoint, our “Ultimate Form.” It is the African diaspora as seen through the lens of Speculative Fiction.

How do you define the Black Fantastic?

The Black Fantastic or Afrofuturism. Which came first? I think, in this case, the relationship is not linear. The Black Fantastic refers to the manner in which Blackness has shaped and reshaped popular culture across the world. It is so completely intertwined with Afrofuturism that the two concepts are often interchangeable. The Black Fantastic, like Afrofuturism, is a noun and a verb. It is also an adjective. Frankly, Black Fantastic is who we of the African diaspora are.

What was the most difficult story/part of your novel to write? Why?

The most difficult part of Queen of Zazzau to write was the god of war. When he and I started his journey, I could only see him through the eyes of my protagonist, and she hated him. He was cold and seemingly cruel. Until, one day, I looked into his heart and saw him for what he truly was. After that, I had to figure out a way to keep his edge without the reader hating him, because he wasn’t the awful person that I had believed him to be, and I didn’t want the readers to think that he was. Fine-tuning his interactions with the main character was difficult, but I think I succeeded.

What’s on your desk?

The real question is: what isn’t on my desk?

What direction would you like to see Afrofuturism and/or the Black Fantastic go? What would you like to see come of this moment of greater recognition?

I would like to see more mainstream speculative fiction written by and featuring the African diaspora. I would like to see the Afrofuturism/Black Fantastic movement spur real change in the way people of color are viewed by the world. I want the world to know that we are so much more than what *they* tell us we are. We are accomplished, we are brilliant, and we can slay orcs as well as any Tolkien hero.

What influences your work? People, other fields, other authors, events, histories?

Everything I come in contact with influences my work. But mostly, I am influenced by the Nigerian culture in which I was raised. Our myths, our fears, our superstitions. All of these things are present in my writing.

What are you working on now?

I am currently working a few projects. Two are in the same series as Queen of Zazzau and will feature African gods and monarchs. The one that has been getting most of my time in the past few weeks, however, is a world-hopping, steampunk, with a side of interracial romance. I thought it would be a straightforward story, but there’s a lot more world-building going on than I had anticipated.

3 Minutes with Nicole, editor of Slay: Stories of the Vampire Noire

Original Photo from Pixabay/Pexels

Welcome the weekend with a closer look at Nicole Givens Kurtz, editor of Slay Vampire Noire and publisher of Mocha Memoirs Press. Below find a bit more about her and delve deeper into the work featured in the Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic Storybundle available until July 2nd.

What’s your general approach to choosing works for an anthology?

My contribution to the Afrofuturism bundle is SLAY: Stories of the Vampire Noire.It is a collection of short stories that feature vampires or slayers from the African diaspora. My approach for choosing the works for this anthology involved seeking stories that had an emotional impact. Stories that lingered long after I had finished reading and stuck like peanut butter, their flavor continuing to permeate long after I’d ingested their content. Of course, I looked for clean drafts and well-rounded stories where the protagonist had agency and was from the diaspora, but the story’s impact mattered more to me with this anthology.

How do you define Afrofuturism?

I define Afrofuturism as creative art (music, art, writing, film) in which those of the African diaspora are depicted prominently in futuristic or alternate settings. An important aspect of Afrofuturism is in its ability to transcend one type of creative outlet. It’s in music, it’s in film, books, lifestyles. It’s a broad term, to be sure, but I think of it as an umbrella to which the other genres gather.

What compels you to keep writing/editing?

Readers and my own stubbornness keep me writing and editing. There are times when the load gets heavy, and I consider putting it down. Publishing is a difficult and challenging industry. My publishing company, Mocha Memoirs Press, has been around for 11 years now. Each year brings new challenges and struggles, and I have considered quitting–many times. Yet what sustains me are reader responses to our works, and my own stubbornness not to give up. I often feel the *break* I need and the press need are just around the corner, so I cannot stop–even when I have rounded many, many corners. LOL.

What are you working on now?

Currently I am working on a science fiction romance story. I just completed draft 0 of a horror novella that may or may not see the light of day. LOL. Mocha Memoirs Press continues to publish bold, fearless fiction. I encourage readers to sign up our newsletter and check out our blog for updated releases at mochamemoirspress.com.

3 Minutes with Michele T. Berger, author of Reenu-You

Original Photo by Lennart Wittstock from Pexels

Michele T. Berger, author of Reenu-You, shares its origin story, what’s next for her, and her influences. Reenu-You and the other fine work in the Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic bundle is available until July 2nd.

What’s the first Afrofuturist/Black Fantastic/Black Scifi work you read? What was the last?

I read Toni Morrison’s Beloved in college and I consider the novel an example of the Black Fantastic. It’s a literary ghost story that ruminates on being, Blackness, death, slavery, memory and history. I read it in a literature class. The novel made an impression on me. The most recent Afrofuturist work I’ve read is Rivers Solomon’s stunning novel The Unkindness of Ghosts. It, too, ruminates on many of the themes explored in Morrison’s work.

Why this story?

Reenu-You is a speculative story with elements of psychological horror that explores what happens when a mysterious virus is seemingly transmitted through a hair care product billed as a natural relaxer. Reenu-You grew from several sources of inspiration. One was watching the drama unfold of a real hair product called ‘Rio’, marketed to women of color in the 1990s. Rio promised an easy and healthy alternative to other products on the market. Soon though women began reporting horrible reactions to Rio including itchy scalps, oozing blisters and significant hair loss. A class action lawsuit revealed that there was nothing natural, at all, about the product. It actually contained a number of highly acidic chemicals.

This news event grabbed me and gave me the inkling for the story. Over several years, I kept asking myself questions about why and how a scandal like that could happen and how different communities might respond to it. I speculated on the mindset of a company that not only deceived the consumer, but endangered their health. I also thought about the consumer, and what desires and longings Rio tapped into. Although I didn’t ever use Rio, I remember the seductive nature of their infomercials quite well. I, like other African American women, was transfixed by their upbeat, exotic marketing that promised an easy and healthy hair treatment.

In watching the events unfold, I thought about how trusting we are as consumers that the products we purchase will be safe. And, also how everyone in the 1990s started to fall for various items labeled ‘natural’. What if that wasn’t the case? What if a hair product that primarily women of color used harbored something deadly?

I’m also fascinated by viruses. I came of age during the height of HIV/AIDS and remember the terror, fear and stigma associated with the virus. For a long time there were conflicting reports about the transmission of HIV/AIDS and its origins. Often conspiracy theories and popular culture filled in the gap.

I wanted to play with the idea of conspiracy and how different communities might respond to a health crisis, especially before the era of ubiquitous cellphones and social media. A virus was a perfect fit.

Viruses are adaptable, disruptive and frequently are medical mysteries. In just the past two decades, we’ve seen Bird Flu, Swine Flu, SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome), Zika, Ebola, and now COVID-19.

I’m also interested in the politics of beauty, female friendships and Black hair culture. In Reenu-You, I can play with these ideas by having different characters reflect on the complexity of their intimate and yet social choices. I love that I get to explore what fascinates and terrifies me, all in one novella.

What influences your work? People, other fields, other authors, events, histories?

Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, Gish Jen, Ntozoke Shange, Octavia Butler, Charles de Lint, Jonathan Lethem, Ursula Le Guin and Elizabeth Hand are writers that I return to again and again to learn from about voice and craft. In the past decade, I’ve been most influenced by the work of Sherri Tepper, Margaret Atwood, Walter Mosely, and Kevin Canty. Writers that I’m currently obsessed with are Cynthia Leitch Smith, Amy Tan, Jeff VanderMeer, Nnedi Okrorafor and Joy Castro. I find myself drawn to the late 1970s and early 1980s (when I was coming of age) and to African American cultural history of the 1920s.

What’s on your desk?

I don’t have a desk. I have an Ikea table that I have made do with for more than twenty years. On it, I currently have two laptops (a Mac and Lenovo, both tend to get glitchy at the same time), precarious piles of papers, journals, post-it notes and the recent book by Gail Carriger, The Heroine’s Journey: For Writers, Readers and Fans of Popular Culture. I also keep heart shaped and gold star stickers at hand. As a fun reward after a session, I’ll put one on my writing calendar. In answering this question, I see I need a bigger reward—a new desk.

What are you working on now?

I’m three drafts into a horror novel that takes place in the North Carolina areas of the Great Dismal Swamp. Prior to the Civil War, the Great Dismal Swamp housed many fugitive slaves and maroon communities. The novel will be published in the fall by Falstaff Books.

3 Minutes with Bill Campbell, co-author of Baaaad Muthaz

Original Photo by @onyx-scopes on Nappy.co

We start the week with Bill Campbell, whose graphic novel Baaaad Muthaz (co-authored with Damian Duffy and illustrated by David Brame) brings the visuals to the Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic bundle until July 2nd. Take it away, Bill.

Describe this work in 3 words.

Spacefunk Pirate Booty!!!

What was the most difficult story/part of your novel to write? Why?

Baaaad Muthaz is an ode to Black music. However, record labels are very strict about quoting music lyrics, so it’s hard to refer to songs without actually using the lyrics. You can only use the songs’ titles. So, a lot of jokes wound up being untold.

What’s your favorite Afrofuturist or Black Fantastic work?

Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo changed my world when I read it back in the day. It informed so much of what I do I’ll have to go with that.

Why this story?

I wanted to do something fun, and I wanted to celebrate the culture. We don’t spend enough time celebrating all the contributions we’ve made to this world.

How do you measure writing success?

There are certain challenges I put before myself with each project—something I don’t think I’d done before. So, if I’m able to pull whatever those challenges are with each project, I’ll generally consider that a success. I don’t know if outside markers really come into play so much (though your ego can play tricks on you) because writing, for me, is such a personal thing.

How do recent challenges of the day (the pandemic, post-Trump/post-Brexit) inform what you’re working on right now? Do they affect the context of this work? If so, how?

I just finished writing a Black superhero graphic novel project that’s heavily influenced by recent events, but I’m not ready to talk about it. It’s an absolutely insane ride, though. I can’t wait to share it with the world.

3 Minutes with Zig Zag Claybourne, Author of The Brothers Jetstream: Leviathan and Afropuffs Are the Antennae of the Universe

Photo by 3Motional Studio from Pexels

Zigs is bringin’ it. I’m gonna get out of the way. (If you want to hear more from this engaging mind and author of 2 books in the bundle, you can get the bundle until July 2nd).

Describe this work in 3 words.

“Oh, it’s on!” (3 more words: exciting, fun, real) (The Brothers Jetstream. For Afro Puffs, the 3 words would be “…and find out.”)

Have you witnessed the Black Fantastic or Afrofuturism in real life? If so, what was it?

Clearest recent example of Afrofuturism at work in my city, Detroit: to address the food deserts (lack of viable grocers) and the technology deserts (internet access—which should never have been commercialized in the first place–isn’t affordable for all, which places lots of Detroit students at a disadvantage) a group of Black community activists and tech activists came together and created free, secure wifi hubs in several of the most neglected areas of the city, along with donating computers. As for the food deserts, community gardens now dot the cityscape in the most beautiful of ways. These are two paths forward for those who faced brick walls. Afrofuturism is DIY. It’s attempting to find a harmonious way that might bring order to chaos.

What was the most difficult story/part of your novel to write? Why?

There’s a scene where a villain murders someone simply because they can. That sense of heartless impunity gutted me because way too much of our real world is exactly like that. People gone for no other reason than a person, a business, a community, a government—wanted them gone. Where’s the respect for our ineffable souls and the dignity of sentience? The story of humanity isn’t meant to be a tragedy.

What’s your favorite Afrofuturist or Black Fantastic work?

Parliament’s Mothership Connection. That entire album is a sci-fi novel spanning worlds, time, and dimensions!

Why this story?

This is the question that gets me bouncing like a hyped boxer. I’ve talked about it before (here for those interested) but short version: I personally wanted an epic tale about Black brothers constantly saving the world, one where they’re always doing it “one last damn time.” I looked for that epic tale. Something wild, something that poked fun at tropes but in a way that brought the reader along for the joke yet had heart. I couldn’t find one. So I squared my shoulders and wrote the ultimate adventure I wanted to read.

As for its sequel AFROPUFFS ARE THE ANTENNAE OF THE UNIVERSE: that was meant from day one to stomp male fragility. If I saw one more fanboi come for a sista (in particular, women in general) in genre…I was ready to act a fool. 2020 called for a story with an all-woman crew; an adventure where a shameless “Kirk” speech delivered by the captain of that crew felt right on time; a sci-fi story wherein idiocy got trounced like it owed everybody money.

Name one darling you killed before the final draft.

Fiona Carel. The crew in PUFFS are the women from The Brothers Jetstream: Leviathan. I wanted to bring Fiona Carel over from The Brothers Jetstream same as I did the crew. Fiona’s Irish, white, and sensitive to the multiverse. I wrote entire sections of her doing angsty multiverse stuff…but ultimately the story said nerp, not this time. As much as I love her character, she distracted from the Black Girl Magic this romp delivers.

What subject do you find most difficult to write about?

I’m not a fan of centering Black trauma, particularly in sci-fi/fantasy arenas. There’s this pernicious notion that pain is intrinsically and specifically tied to Black skin, be it on the Continent or via the diaspora, which tells me that regardless of the surrounding plot, the only story too many people want to hear from us is how we deal with the “pain” of being Black. Listen, I grew up listening to Earth Wind & Fire and Prince; I got the rhythms of the ancients in me! I can bring the thunder and lightning, but I play in the joyous rain.

What direction would you like to see Afrofuturism and/or the Black Fantastic go? What would you like to see come of this moment of greater recognition?

My hope is that readers realize Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic (which damn well needs to be a band name) are more than solely entertainment to pass the time, they’re building blocks to actual social change far past the status quo. Whether comedy, adventure, fantasy, drama, romance–art is meant to connect us to something more than we started with.

How do you measure writing success?

First, by how much fun I had with the story. Second, by how satisfied I am with the story’s soul upon completion. Third, did readers feel like I honored their time? Anything after that is whipped cream on top of pie.

What’s your approach to worldbuilding?

I’m a fan of the less-is-more approach. As a writer and a reader, I like to wander a story’s playground to find interesting toys and attractions. If I’m reading your zombie sci fi novel I don’t want a page of exposition telling me about the planet’s atmosphere, the evil mining corporation that abandoned folks, and the marital backstories of the two main protagonists. I want “There weren’t enough of us left to bury the bodies…”

What’s the first Afrofuturist/Black Fantastic/Black Scifi work you read? What was the last?

Dhalgren by Samuel Delany was the first, a book which opened me to wonderful new ways to tell a story. The Space Between Worlds by Micaiah Johnson is the latest, a wonderful journey through the multiverse. Both books share an expansive sense of scope and character, which I love.

What are you working on now?

In March 2020 I had a short story published at GigaNotosaurus about a mother and daughter witch team from a secondary-world version of Africa traveling the world. It was called “The Air in My House Tastes Like Sugar”. The characters spoke to me so much I wanted to see what they did next. Result? A fantasy novel about this mother & young daughter having the adventure of their lives.

What compels you to keep writing/editing?

Questions. Not understanding things. Writing helps me see the world’s bones and tendons at work. I may leave this world not having figured a single thing out, but at least I can say I made the attempt.

3 Minutes with Zelda, Co-Editor of Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora

Original Photo from Pexels

While the Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic storybundle is going on (until July 2nd), I’ll be sharing a little about some of the editors and other authors in the bundle. Zelda Knight, coeditor of Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora kicks us off.

Describe this work in 3 words.

African / Diasporic Unity

Editors, what’s your general approach to choosing works for an anthology?

When selecting works for an anthology, I always go through a similar mental checklist: does it follow the requirements, is it on theme, and does it mesh well with other accepted works or offer a contrasting view? If a work satisfies all three, then I take the time to really dive in. I’m mindful of how hard it is to put something you created before a stranger’s eyes, and try to keep that in mind even when I have sharp critiques.

What compels you to keep writing/editing?

There are always new worlds to discover and voices that need to be heard. If gatekeepers aren’t going to publish them, I can’t complain that these stories aren’t being told when I have the expertise to make that happen. Indie presses and authors are always setting the mainstream trend.

The world is awash in terms right now: Afrofuturism, Africanfuturism, Black Speculative Fiction, the Black Fantastic, Astroblackness, etc. Do they matter? If so, do they do justice to the diaspora? If not, how might we as authors and editors lead a change? Feel free to offer any new terms you think would expand and/or deepen the concept.

I think so to some people. As long as authors are actually taking the time to properly cite the foremothers, forefathers, and so on of these terms (in particular Afrofuturism that is receiving a lot of undue criticism as of late), I don’t personally care. No one term can “do justice” to the diaspora because the African Diaspora is truly global, and many are created with specific experiences in mind. The experience of people of African descent are linked but not identical, you know? I’m personally of the philosophy that authors should (a) use what works for them, (b) respect the work of who came before them before launching critiques, and (c) the publishing world should take time to respect which labels people place on their own works. The last would be the real change.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on personal work in the sci-fi and fantasy romance realm all the time. I’d recommend my novelette, Zephyr’s Curse, if you want a small taste of the stories I tell. Anthology-wise, I’m co-editing a number of Afrocentric anthologies with Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki and Sheree Renée Thomas!

3 Minutes with Ginn, Author of The Long Past & Other Stories

Original Photo by Anna Shvets from Pexels

There are only 3 days left for the bundle. So we end the 3 Minutes With series for the Innovative Worlds storybundle on a warm and wonderful note, with the incomparable Ginn Hale who shares her insightful views on necessary innovation, speculative fiction’s roles and gives us a glimpse into her writing life.

What innovation do you think the world most needs right now? The US?

GH: Hmm that’s a tough question—but fascinating.

Pondering it, I just realized that I often limit my idea of innovation to science alone. DNA sequencing, processor speeds, artificial intelligence, gene therapies… But innovations in social values and laws— Civil Rights, Gay Rights, Women’s Rights, the passage of the ADA—are the ones that have most improved my own life and the lives of my friends and family.

It doesn’t matter what great scientific leaps we make if they only serve to prop up inequitable societies.

Looking at it that way maybe the world might benefit most from a new economic ideal. Because right now, the most powerful nations seem driven by their economies and the current systems appear to foster worldwide inequity, reward the human exploitation and the destruction of the environment. We measure nations in terms of GDPs and devalue individuals as if they were nothing but credit scores and interest rates. When in reality our natural world and the people we share it with are the very things that enrich each of our lives the most.

What we badly need is a new concept of wealth—one that is measured by community wellbeing, human equity and environmental health.

I don’t know how such an economy would function. What would commerce look like within it? That’s where the spark of inspiration and innovation are needed—but I’d be truly excited to find out.

Does speculative fiction have a role in innovation? If so, what is it?

GH: I think that it does. I know people often cite occasions when fiction has inspired people to realize an invention or a profession. But I think fiction—particularly fantastical and speculative fiction, encourages innovation in another way as well. It helps them imagining the improbable and impossible as achievable possibilities. When readers engage with speculative fiction they practice thinking beyond the world they know to explore new paradigms. They experience alien problems and otherworldly solutions. And above all, they get to enjoy that sense of engaging with the new, unknown and unexpected. All of which, I believe, fosters a greater comfort and excitement with original concepts and innovations.

What’s on your desk?

GH: A cat. Beneath it, I can just about see my keyboard. ☺

Why this story?

GH: Because it’s the story my wife asked for. She wanted a fantastical take on the American west, where she grew up. But one that reflected the actual diversity of our friends, families and their histories… And then she threw in the request for dinosaurs! ☺

Name one darling you killed before the final draft.

GH: I desperately wanted to include a section following the adventures of “Lady” Honoria Aster, a genderfluid, 50 year-old mage and secret agent, who makes an appearance in the first section of the collection. But in a book already brimming with dinosaurs, magic and clockwork, Honoria’s trek around the world and steady transformation from spy to rebel would have filled at least one entire volume all on its own. I couldn’t make it fit, no matter how much I trimmed. So, in the end, I had to settle for mentioning the publication of H. Astor’s memoirs in the third section—maybe just to assure myself that they might someday become a reality. ☺

How do you measure writing success?

GH: I think a piece of writing is a success if it touches another person. It doesn’t have to make money or win awards—those things are lovely— it just has to speak, truly to another soul. A piece of writing can be a success even when it’s nothing more than text from my wife, telling me that she’s on her way home and that she loves me.

Do you have any writing tics?

GH: Oh yes… So many that I sometimes fear that I’m just a collection of tics, that my genius editors manage to trim into the guise of a real and whole writer. ☺

What influences your work? People, other fields, other authors, events, histories?

GH: I love science and the natural world. My Instagram is mostly pictures of plants I’ve encountered on my various rambles. My poor wife has to put up with an ever-expanding tree—named Mike—that has lived and moved with us for the past 25 years. Those things are what most inform the settings of my stories. The characters however are nearly all based on people in and around my community.

What is it about books that fascinates you?

GH: Maybe it’s because I’m dyslexic and reading has been such a hard-won skill for me, but I retain a real sense of wonder about books, and written words in particular. For the longest time books were these opaque objects–collections of pages decorated with a variety of repeating marks. Puzzle boxes, that I couldn’t figure out but every time I picked one up I could feel something secret, something amazing rolling around inside.

I remember struggling to make all the little symbols stay in place and tell me their names. It was so frustrating to fail again and again, but also so enticing to know that there might be wonders hidden in these tomes, if only I could understand them.

Then came that instant of astounding transformation—a day when those marks and their arrangement suddenly spoke to me, without making a sound. I read a word and it lit a vision in my eyes as I looked at it. I felt the faintly pebbled surface of eggshell, still warm from beneath a hen’s body. It felt like a feat of pure magic.

Of course now I feel a little embarrassed to admit that reading the three-letter sequence ‘E-G-G’ moved me to tears. But the truth is that instant felt so astonishing, so triumphant, that the sense of wonder has never completely left me. Even now I find myself gazing at some random books on a library shelf and being filled with fantastic anticipation for all the ideas, images and sensations that they might gift me if I choose to open one of them.

And when I write—as slowly as I do—I always hope that someday one of my stories might provide the same magical experience for someone else.

3 Minutes with Bill, Co-Editor of Future Fictions: New Dimensions in International Science Fiction

Bill Campbell, co-editor of Future Fictions, included in the Innovative Worlds storybundle available until August 27th, cracks open the door on his motivations, process, and thoughts on speculative fiction and innovation.

What’s your favorite innovation of the last 25 years? The last 5?

BC: I’m not sure. However, another music fiend and I were talking the other day about how much we love that we can access our entire music collections on our phone. If the rest of the world weren’t so clearly going to hell, I’d call this heaven!

Do you have any writing tics?

BC: The thing that annoys me most about myself, writing wise, is that before I start writing any project, I go through this excruciating period of self-flagellation where I think I’m the dumbest person on the planet and have no business writing. It takes a minute to snap out of it, but in an odd way it gives me hope because then I know I’m ready to start writing.

Does speculative fiction have a role in innovation? If so, what is it?

BC: Whenever I run into someone who says that they don’t like speculative fiction, I tell them whatever device, etc., they see in the world was first thought up in a book. But perhaps more importantly, there are questions and problems in the past, present, and future that many authors have wrestled with in their works. That’s what makes the genre so fascinating. Perhaps asking those questions is our role.

What’s on your desk?

BC: My head. I’m exhausted.

What’s the first book you really connected with? Made you cry? Laugh out loud?

BC: For me it was all about S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders. For more reasons than I care to go into here, I pretty much felt like an outsider everywhere I went, and I definitely understood what it was like having to fight for your space. There I was, 12 years old, desperately wanting to be in a gang. Thank goodness I grew up in the suburbs of Pittsburgh where there were none. Who knows what would’ve happened to me otherwise.

3 Minutes with Eileen, Author of Questionable Practices

Original Photo by Engin Akyurt from Pexels

If you’re not familiar with Eileen Gunn’s Question Practices it’d be best if you were. Save yourself the trouble such ignorance causes. The Innovative Worlds bundle can help you out until August 27th. For now do yourself a favor and spend the next few minutes familiarizing yourself with her thoughts.

Does speculative fiction have a role in innovation? If so, what is it?

EG: Speculative fiction has a number of roles in innovation. (1) To young readers, at a stage when their ideas about the world are being formed, it celebrates innovation as an important force in creating our world, and it frequently makes the point that young people can drive innovation, that they can come up with ideas that make a positive difference in people’s lives. A number of prominent scientists and technologists have been inspired to enter their chosen field by reading speculative fiction as children. (2) For all readers, speculative fiction generally inculcates the idea that innovations, new ways of doing things, are to be encouraged, not feared. Humanity is always pulled between the safety of the old, tried-and-true ways of doing things, and the adventure of new, possibly risky ideas and techniques. Speculative fiction often encourages people to accept risk and do something new. (3) The problems and solutions envisioned in speculative stories have inspired scientists, technologists, social thinkers, and many other innovators to tackle those problems themselves. Sometimes their solutions were congruent with those in the stories, and sometimes they were very different, but the innovator’s attention was drawn to the problem by speculative fiction.

What’s your favorite innovation of the last 25 years? The last 5?

EG: Of the past 25 years? I’m guessing my favorite innovation is that whatchamacallit that holds my schedule and all my music and books and photos, and lets me cruise the Internet from anywhere in the world, and tells me exactly where I am and how to get to where I’d rather to be, and instantly translates dozens of languages, soI read all the menus in Chengdu and have friendly conversations with people whose language I don’t speak. That innovation.

Of the past 5 years? That’s a hard one, but probably those do-it-yourself tattoos that are like movies all over my body and they glow in the dark and I can turn them off and on. Oh, wait, we don’t get those until [checks watch] 2029. So I guess, for my favorite innovation of the past five years, I’m gonna hafta go with Zoom, which has changed my life radically for the good in the past five months. All of a sudden, I can stay in touch with my far-flung friends and relations, teach classes, and attend events all over the world from my living room. We’ve had video calls and Skype and all kinds of awkward ways of staying in visual touch with geographically distant people, but Zoom, with its remarkably short learning curve, has scaled up gracefully from 10 million calls a day last December to 300 million calls a day at the beginning of August.

Right now in the US, there’s the struggle with the pandemic, what some are calling a racial reckoning and a hotly contested, crucial race to decide who will be the next president, what part can fiction and storytelling play in such times? How can it contribute or detract?

Ursula Le Guin once said to me, “Fiction is a road to imagining a different world.” Speculative fiction, in its broadest sense, is about different worlds, about the idea that things are not the same everywhere, and that things change. The world is malleable, and we can change it and change with it. There are many SF novels about people surviving disasters, stories of ordinary people who see their comfortable lives end and rise to meet the challenge, or who have difficult lives and draw on special skills and reserves of strength. At its most optimistic, this kind of fiction imagines new social structures and societies in which race and money and power work differently than they do in our own time and place. At its most pessimistic, it suggests that things will get worse and only the tough will survive. Perhaps the optimistic books give us something to work towards in these grim times, and the pessimistic, something to try to avoid. Either way, SF can give the anodyne of escape from the present, a warning of how quickly things could get worse, and a reminder that, no matter what, things will change.

What was the most difficult story/part of your novel to write? Why?

The final story in my collection, “Phantom Pain,” was definitely the most difficult to write. I drew on my father’s reminiscences and fiction about his experiences in World War II and on the way physical and mental pain work in the human body. I read a number of books on the physiology of pain, some of which were philosophical and almost poetic. Pain, after all, is doing its best to keep us alive and healthy, and yet we do not welcome it. It’s a story that took me more than ten years to write, and it was worth the journey.

What’s on your desk?

Really, what isn’t on my desk? All the usual—a mammoth computer, a desk-lamp that is not completely reliable, an iPad, a 15-year-old iPod full of music, printouts of a short story and an essay I’m working on, an empty coffee cup, a large tape dispenser that appears to be filled with sand, two identical flashlights, only one of which works, a satiric sketch of Mark Twain in front of the footlights, a box of Pirate bandaids with skulls on them, a full-head mask of a red-faced demon with shaggy black hair, and a stack of five brilliant books by Ken MacLeod.

What’s the first book you really connected with? Made you cry? Laugh out loud?

It was James M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, Retold for Young People, by May Barton, illustrated by Mable Lucie Atwell. I was seven, and my teacher had given it to me from a stack of old kids’ books she’d found in a cabinet. The illustrations were adorable, and skewed my aesthetic sense to the twee for nearly a decade. May Barton’s authorized rewriting of Barrie was pitch-perfect. I wore that book to a nubbin. I re-read it over and over and laughed every time the Lost Boys scared off the wolves by turning their backs on them and looking at them through their legs, and I teared up every time Peter waited on the rock to die as the tide came in. I still think that to die would be a really big adventure. I still believe that it’s possible for people, like Peter, to be valiant and completely self-centered at the same time. And I’m still sorry that we all have to grow up.

3 Minutes with JD, Author of Moonflower, Nightshade, All the Hours of the Day

JD Scott — whose debut collection, Moonflower, Nightshade, All the Hours of the Day is included in the Innovative Worlds storybundle, available until August 27th, shares a few views about innovation and some of the challenges of completing the collection.

JD Scott — whose debut collection, Moonflower, Nightshade, All the Hours of the Day is included in the Innovative Worlds storybundle, available until August 27th, shares a few views about innovation and some of the challenges of completing the collection.

Does speculative fiction have a role in innovation? If so, what is it?

JDS: Of course—being able to ask “what if…?” is an activation of the imagination. To be able to imagine new worlds or better worlds can create pathways or percussions that interact with other parts of our culture. Speculative writers exist in a type of biomimicry, where our questions can lead to answers by thinkers in other fields.

What innovation does publishing most need right now?

JDS: Public conversations that have happened throughout 2020 so far have shed light on what many of us have already talked about in private: publishing needs more equity and transparency from the top-down. Publishers, agents, and editors should be actively seeking out work from BIPOC and trans writers. At the same time, we need more transparency with how these writers are being approached and being paid beside their counterparts. Similarly, one way to do this is to hire agents and editors who have typically been left out of the conversation. The annual “Diversity in Publishing” statistics reveals that publishing continues to be overwhelmingly made up of cis, heterosexual, non-disabled, straight white women. Making space for different voices to work in publishing will have impacts on the writers who are being published.

Beyond the writers themselves, I also wish there was more bridge-building between the small press and the Big Five, between indies and academies. There are strategies and ideas from these individual nodes that might be useful in other spaces if more cross-pollination occurred.

What was the most difficult story to write? Why?

JDS: Each story in the collection had their own individual challenges, but “After the End Came the Mall, and the Mall Was Everything” comes to mind specifically because of its length. I wrote poetry before I ever made an attempt at fiction, so there was a certain amount of comfort in concision for me. This was the first truly long-form work I wrote: a novella of 20,000+ words. It leans into many different genres, from adventure to fantasy to horror to fairy tales to literary fiction. I had to challenge myself to approach my relationship with fiction in a new way because of the length, considering a type of magnitude and perseverance that had eluded me previously.

Describe this work in 3 words.

JDS: Elusive, deceptive, zesty.

Name one darling you killed before the final draft.

JDS: Originally the story collection was twelve pieces, and it was edited down to ten. Coincidentally, one of the darlings that was killed was arguably the most speculative story. It involved a world in which humans’ ages were frozen and natural death was abolished. In the story, it’s found out that a virus found in common pigeons is unfreezing people, causing them to resume aging. The main characters, a couple, face challenges when one of them continues to harbor pet pigeons on their city apartment’s rooftop. Unfortunately, I felt the chronology was too confusing and that the characters’ relationships paralleled other relationships that were handled better in other stories, so the darling was killed.

Do you have any writing tics?

JDS: Pacing in circles at home while I’m thinking/writing in my head is something I’ve always done.

What’s your approach to worldbuilding?

JDS: I find that worldbuilding of the intuitive sort works best for me—something that happens on the page—an idea in the moment. There is something pleasurable about meticulously planning elsewhere, but I find those oneiric activities—at least in my case—can go too far to the point where the real writing never gets started because too much time is spent in the margins and side notes tracking minutiae.

3 Minutes with Larissa, Author of When Fox Is A Thousand

Original Photo by Martin Damboldt from Pexels

Next up from the Innovative Worlds storybundle we have award-winning author, Larissa Lai whose novel When Fox Is A Thousand is included. She stops by to drop knowledge about some innovations the world needs right now and some of her writing goals.

What innovation do you think the world most needs right now? The US?

LL: I think the world needs a viable imagination for how to get out of deepening patterns of strong arm rule, cruelty and oppression. It needs a form of media that people will write/read/watch/hear/speak to/listen to with engagement and interest that at the same time allows for and encourages complex, nuanced, compassionate and respectful conversation. These things would be good for the US too.

Does speculative fiction have a role in innovation? If so, what is it?

LL: I think speculative fiction is key to positive social change. Fiction writers in general have the gift and responsibility of being able to think dialogically. Speculative fiction writers have the additional gift and responsibility of being able to imagine new or different worlds, technologies, and futures. The speculative fiction traditions of utopia, dystopia and what the Tom Moylan has called critical utopia can be especially useful right now.

What’s your favorite innovation of the last 25 years? The last 5?

LL: How about the last 50? I like the brooder in Marge Piercy’s Woman on the Edge of Time. Not because I actually want one, but I really appreciate the social direction that innovation turned us towards. This is a fictional innovation obviously.

Who’s the greatest innovator of your lifetime (public or personal)?

LL: Octavia Butler, because of her capacities to dream us into the future in relationship across racial difference, as imperfect but compassionate beings.

What innovation does publishing most need right now?

LL: We need a more robust, intelligent, compassionate, generous, and broadly engaged review culture than what we have right now, one that can productively expand and deepen our conversation about books. I hope this will expand and deepen the way we live together in these difficult times.

Right now in the US, there’s the struggle with the pandemic, what some are calling a racial reckoning and a hotly contested, crucial race to decide who will be the next president, what part can fiction and storytelling play in such times? How can it contribute or detract?

LL: I think the social speculative fiction strain that ran strong in the 1970s and at present can be really useful to help us think through the consequences of any potential choices, actions, or organizing work we do right now. I think particularly of Ursula LeGuin and her idea of the literary experiment, which changes one (or more) things in our present world and uses the novel to test it out. One can test out things in in novels without hurting real people. But of course, because they are part of the real world, novels can spark things in it that can change it. So we must be careful!

What was the most difficult story/part of your novel to write? Why?

LL: The contemporary “Artemis” sections. These were difficult perhaps because they were closest to home, at the time of writing.

How do you measure writing success?

LL: When I wrote When Fox Is a Thousand, I wanted it to empower other young people like myself (as I was then). By this I mean the generally BIPOC, GBLTQ2S+ communities through which I moved (and still move). I wanted other young Asian women to find something of and for themselves in the book. These days, while those concerns are still important, I want my writing to more than that. By more, I mean I want it to build relationships. If it also gives us an inkling of how to live better together, that would be wonderful.

dash—dash

3 Minutes with Maurice, Author of Pimp My Airship

Original photo by Tim Gouw on Pexels

While the Innovative Worlds storybundle is going on (until August 27th), I’ll be sharing a little about some of the other authors in the bundle. We begin with Maurice Broaddus. His novel, Pimp My Airship, which started as joke on Twitter but evolved into something much more, is in the bundle.

What innovation do you think the world most needs right now? The US?

MB: A new economic system. One that values people and relationships first. The arts and teachers as the bedrock of our culture and way of doing things. The innovation needed is social: how we see, know, and celebrate people.

Does speculative fiction have a role in innovation? If so, what is it?

MB: Absolutely. We’re the dreamers. We cast the vision of what life, the future, different worlds could look like. People have trouble charting a course when they have no idea where they are going. Writers create a roadmap for what we could work toward.

Right now in the US, there’s the struggle with the pandemic, what some are calling a racial reckoning and a hotly contested, crucial race to decide who will be the next president, what part can fiction and storytelling play in such times? How can it contribute or detract?

MB: We’re also the mirror. One of the things we often talk about is how Afrofuturism is rooted in the past, critiques the present, all while imagining a better tomorrow. Being rooted in the past means being aware of the history, how we got here. All the stories. Critiquing the present by continuing to tell the stories, especially from those corners and peoples who have been marginalized (because nothing better illustrates a power/empire than how it treats the most powerless of its citizens). And imaging a better tomorrow … to paraphrase author Tananarive Due, even the act of imagining ourselves in the future is an act of resistance. We dream and we resist, that’s our role.

What was the most difficult story/part of your novel to write? Why?

MB: Pimp My Airship had two areas that were difficult. The first was that it was a steampunk story with an all-black cast. That hadn’t been done. I wasn’t certain what the rules/conventions were of the genre. Then ultimately I had to trust myself and toss out the playbook (since playbooks rarely serve us anyway). The second was turning the original short story into this novel. I’d never done that before. So it became an exercise in continuing to push my imagination.

What’s on your desk?

MB: A notepad. A pen. A superhero mat. A nameplate that reads “I’m Kind of a Big Deal” (a present from my wife). Books: The Wretched of the Earth (Frantz Fanon). Sapiens (Yuval Noah Harari). Blended (Sharon M. Draper). The Hate U Give (Angie Thomas). The City We Became (N.K. Jemisin).

How do you measure writing success?

MB: Did I finish the story.

Do you have any writing tics?

MB: I write long hand. On colored tablets. (Today’s color is green … do you know how hard it is to find green notepads?)

What’s your approach to worldbuilding?

MB: I have one job: to out-imagine the reader. So every writing project, it’s “Game on!”

A Minute with Authors and Architects of Innovative Worlds

Now that the bundle has launched a bit of context: I wanted to put together an Innovative Worlds storybundle for reasons both personal and professional. All of those reasons pertain to all of us. Fitting then that we start the author conversations that I enjoy as much as curating the bundle with the responses of some of the excellent authors and editors who have been gracious enough to take part. Here are their answers to “Does speculative fiction have a role to play in innovation? If so, what is it?”

JD Scott: Of course—being able to ask “what if…?” is an activation of the imagination. To be able to imagine new worlds or better worlds can create pathways or percussions that interact with other parts of our culture. Speculative writers exist in a type of biomimicry, where our questions can lead to answers by thinkers in other fields.

Larissa Lai: I think speculative fiction is key to positive social change. Fiction writers in general have the gift and responsibility of being able to think dialogically. Speculative fiction writers have the additional gift and responsibility of being able to imagine new or different worlds, technologies, and futures. The speculative fiction traditions of utopia, dystopia and what Tom Moylan has called critical utopia can be especially useful right now.

Bill Campbell: Whenever I run into someone who says that they don’t like speculative fiction, I tell them whatever device, etc., they see in the world was first thought up in a book. But perhaps more importantly, there are questions and problems in the past, present, and future that many authors have wrestled with in their works. That’s what makes the genre so fascinating. Perhaps asking those questions is our role.

Ginn Hale: I think that it does. I know people often cite occasions when fiction has inspired people to realize an invention or a profession. But I think fiction—particularly fantastical and speculative fiction, encourages innovation in another way as well. It helps them imagine the improbable and impossible as achievable possibilities. When readers engage with speculative fiction they practice thinking beyond the world they know to explore new paradigms. They experience alien problems and otherworldly solutions. And above all, they get to enjoy that sense of engaging with the new, unknown and unexpected. All of which, I believe, fosters a greater comfort and excitement with original concepts and innovations.

Eileen Gunn: Speculative fiction has a number of roles in innovation. (1) To young readers, at a stage when their ideas about the world are being formed, it celebrates innovation as an important force in creating our world, and it frequently makes the point that young people can drive innovation, that they can come up with ideas that make a positive difference in people’s lives. A number of prominent scientists and technologists have been inspired to enter their chosen field by reading speculative fiction as children. (2) For all readers, speculative fiction generally inculcates the idea that innovations, new ways of doing things, are to be encouraged, not feared. Humanity is always pulled between the safety of the old, tried-and-true ways of doing things, and the adventure of new, possibly risky ideas and techniques. Speculative fiction often encourages people to accept risk and do something new. (3) The problems and solutions envisioned in speculative stories have inspired scientists, technologists, social thinkers, and many other innovators to tackle those problems themselves. Sometimes their solutions were congruent with those in the stories, and sometimes they were very different, but the innovator’s attention was drawn to the problem by speculative fiction.

Maurice Broaddus: Absolutely. We’re the dreamers. We cast the vision of what life, the future, different worlds could look like. People have trouble charting a course when they have no idea where they are going. Writers create a roadmap for what we could work toward.

And tomorrow we journey down that road, beginning where we end today: 3 Minutes with Maurice Broaddus. If you’d like to go a bit further the bundle is available until August 27th.

3 Minutes with Andrea, Author of Will Do Magic for Small Change

With just a little over a day left on the Afrofuturism storybundle Andrea Hairston shares her thoughts on working in different forms and the intersection of Will Do Magic

With just a little over a day left on the Afrofuturism storybundle Andrea Hairston shares her thoughts on working in different forms and the intersection of Will Do Magic

How does being a playwright inform your work?

I am a dramatic storyteller. Drama is about the poetry of action. Meaning is in the juxtaposition of actions, in the clash of character choices and consequences. Theatre is about embodying the other—acting who you are not, writing another world, experimenting with reality. Theatre takes me right to speculative world building and stories beyond mimetic realism.

Why this story?

Stories come to me. They have to be written. I honor that.

I’d been thinking about the Dahomey (West African) warrior women who supposedly appeared at the Chicago World’s Fair for a long time. There’s a moment in an earlier novel, Redwood and Wildfire, where they also appear. So why not have an alien from another dimension meet them and learn the world from their perspective? Why not connect Redwood and Wildfire’s granddaughter with the alien?

Describe this work in 3 words.

Alien Ancestor Theatre-magic

How do you measure writing success?

Success is telling the stories you want to tell, how you want to tell them.

Success is challenging yourself and showing up every day for that challenge.

Success is having the generosity of spirit and the humility to connect with and support other artists.

Success is never giving up on getting better, but taking pleasure in what you have achieved.

3 Minutes with Ayize, Author of The Liminal People

Ayize Jama-Everett’s The Liminal People is also featured in the Afrofuturism Storybundle. Here, a closer look at writing and the work:

How does liminality manifest in your life?

How does it not?! I’m forever between the now and the later, the done and the doing. It’s a character trait flaw that makes contentment an accomplishment for others and not myself. Despite being born black in Harlem to politically minded folks, I used to refer to myself as a Black Cultural Refugee, before black geeks became cool. I have three master’s degrees and no Ph.D. I’m in the middle of the world and my understanding of it. Yes, liminality is manifested in my life.

Describe this work in 3 words.

Traveled. Troubled. Family.

Why this story?

This story was a compromise between the expansive multi-dimensional tale I wanted to tell and the intimate close narrative that the epic needed to be based in. It’s been a long and strange balancing act.

What subject do you find most difficult to write about? The most effortless?

Can they be the same thing? I love writing about fights and food. My next novel should be about food fights. But the choreography of physical combat and the innate sensualness of anything that is offered to the mouth make the writing effortless and enjoyable. I tend to stay away from real life events though I have experimented. Nonfiction is probably something I should push myself to write more but I think I need to hang in some plain old narrative fiction for a while before I do that. The idea that a mundane life can be worthy of insight given the proper attention to the craft of writing is not revelatory but expansive for a kid who grew up reading sci-fi and comics.

3 Minutes with Nicole, author of Silenced

From the Afrofuturism Storybundle, we have Nicole Givens Kurtz, author of Silenced on speculative mystery, this particular one, Afrofuturism and more.

What are 3 questions/answers on the FAQ page of Silenced?

What is a private inspector? An inspector in a detective, but in the future, they’re all called inspectors due to a change in governance from the United States to meddling by the British.

Why are the United States divided? The U.S. is divided after a second Civil War. Each territory is governed however they see fit. Some territories have dictators. Others have a socialist system. It depends on the territory. In Cybil Lewis’s The District, the governor acts as the leader of the territory in conjunction with Congress.

What weapons does Cybil use? Cybil has two guns, a lasergun 350 and a pug, which is a short revolver with laserpowered cartridges that must be charged.

What was the most difficult story/part of your novel to write? Why?

The most difficult part of Silenced was the death scene. I won’t give away who dies, but the death hurt my heart. Like Cybil, I wanted that character to live, to fulfill the promise they had, but it didn’t happen that way. I cried after I wrote it and I pushed back from my computer. I had to take a few minutes to collect myself. I skipped that chapter often when I re-read the book. It happens so often in real life, that it hit me hard, square in the feels.

How about small press/indie publishing, what do you find most difficult?

I’m a hybrid author. That means I am both self-published and published by a publishing company. The challenges of both are marketing, finding an audience, and sustainability.

What draws you to speculative mystery?

What draws me to speculative mystery is the thrill of the hunt. The chase to discover who is responsible for the crime. Can our protagonist discover the culprit? How does she/he discover the culprit? I love the introductions into worlds of light and dark.

Do you have any writing tics?

I do have writing tics. I cannot write if my desk is messy. I am frozen with anxiety. I also have a hard time writing if my handwriting is messy or sloppy. I will rip the paper off the legal pad and rewrite it. I do this often as I tend to cross out items as I write longhand!

What direction would you like to see Afrofuturism go in? What would you like to see come of this Afrofuturism moment?

I would like to see Afrofuturism continue to incorporate all areas of media. I would love to see more TV and film media embrace authentic Afrofuturism. Black Panther had the backing of Disney, but many independent filmmakers are producing quality works but cannot get the distribution. How do we harness that hunger to our advantage? How do we connect those people who adored Black Panther to our independent works? I want to see the movement embrace all Afro-centric stories, not just those rooted in Africa, but from the other countries in the diaspora, including the U.S. Most importantly, there is amazing work being created in comics, novels, films, and music, but have not reached the audience necessary to be as big as I think it can be.

3 Minutes with Ivor, Editor of AfroSF

Next up from the Afrofuturism storybundle is Ivor W. Hartmann – editor, writer, publisher and visual artist – on the AfroSF anthology series and editing’s intersections with writing.

In what way ways has the AfroSF anthology series surprised you?

When the first AfroSF came out in 2012, I was blown away by the warm and welcoming reception it received from the international SF community; it was very heartening. As writers we are just trying to do our own thing, and back then hardly anyone was publishing our SF locally or internationally, so we just did it ourselves. So this reception meant a lot, that we could thrive locally and internationally, that there was a confirmed positive interest in what we were doing.

Describe this work in 3 words.

African Science Fiction.

Why this work?

Science Fiction is the only genre that enables African writers to envision a future from our African perspective. Moreover, it does this in a way that is not purely academic and so provides a vision that is readily understandable through a fictional context. The value of this envisioning for any developing country, or in our case continent, cannot be overstated nor negated. If you can’t see and relay an understandable vision of the future, your future will be co-opted by someone else’s vision, one that will not necessarily have your best interests at heart. Thus, Science Fiction by African writers is of paramount importance to the development and future of our continent.

You write and edit. In what ways does each inform your work in the other?

I think they work very well together; writing makes you a better editor and editing makes you a better writer. The tricky part, so tricky, is having a healthy time balance between them, something I have yet to achieve. As an editor understanding fully the writing process—the massive space stories take up in one’s mind and how so little of that makes the page, and yet without it the page would be bare—is invaluable. Likewise as a writer fully understanding the editing process—the quest to help refine a story to its best possible form whilst fully retaining the writer’s voice—is an imperative, to know that there is no writer who can fully and properly edit themselves, how an editor’s outside perspective is integral to the writing process.

3 Minutes with Nisi, Author of Filter House

While the Afrofuturism storybundle is going on (until June 7th), I’ll be sharing a little about some of the other authors in the bundle. We begin with Nisi Shawl. Her collection, Filter House, winner of the Tiptree Award is included.

What are 3 questions/answers on the FAQ page of Filter House?

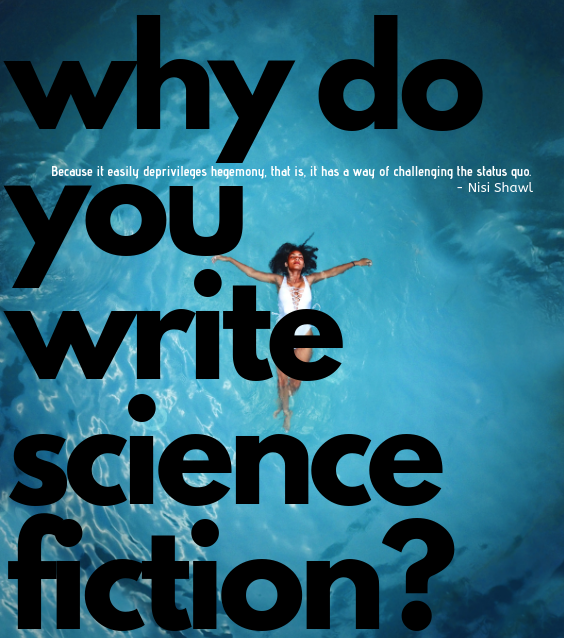

- Why do you write science fiction?

Because it easily deprivileges hegemony, that is, it has a way of challenging the status quo.

- What’s a common theme in your work?

That’s for you to figure out. Themes are what readers experience, not what writers intend.

- Who are your literary influences?

Colette, Samuel R. Delany, Raymond Chandler (token het male), George Eliot, Connie Willis, Dorothy Dunnett, Joanna Russ, Suzy McKee Charnas, C.J. Cherryh, E. Nesbit, and Nalo Hopkinson.

Describe this work in 3 words.

Voices harmonizing with strangeness. Sorry. That’s four. Trying again: strangely harmonizing voices.

Why these stories?

Filter House is a collection of stories Timmi chose. I think she put them together to show how the journey to selfhood can work for women of African descent. That’s my guess.

What’s your approach to creating a collection? For instance, some may compile their works letting each work speak for itself, perhaps even letting their editors decide on the order, while others may attempt to focus more on the work as a whole and work towards that effect.

I have never actually created a collection of my own work. So far there have been two; both were assembled by L. Timmel Duchamp.

You just received the Solstice Award (Well deserved and congratulations!) and Filter House I believe was your first award winner. So you have a unique perspective in gaining recognition but also recognizing what work may remain or has already been accomplished. What’s your read on this moment in SF as it pertains to Afrofuturism? If it’s helpful to unpack that a bit: What direction would you like to see Afrofuturism go in? What would you like to see come of this Afrofuturism moment?

Thank you for the congratulations! Yes, I have seen immense changes in the reception for Afrofuturist fiction over the course of my working life. The audience has grown, and has proven itself a financial force to be reckoned with; the pool of creators has grown and has gotten more widely recognized than in my youth; the gatekeepers are more receptive now. What I’d like to see going forward is further expansion: Afrofuturist cuisine, Afrofuturist architecture, Afrofuturist politics! More of this stuff, and more different kinds of it!